How Arnold Trained - An Evolution

Arnold Schwarzenegger asked me to collaborate on his Encyclopedia of Modern Bodybuilding back in the mid-1980s. The idea of the book was to sum up the total knowledge of bodybuilding training and diet as was understood at the time, along with comments, history, and insights based on Arnold’s long history as a successful bodybuilding champion. The book, Arnold was determined, should be useful to everyone from pro champs to beginners just working out in the gym for the first time.

The Encyclopedia was an enormous success and became the “bible” of the bodybuilding method, the main go-to reference for creating the best muscular physique possible. But times change, the world moves on, and in the world of bodybuilding, there has been enormous progress since the book was published in knowledge and practice in effective weight training and the most efficient approaches to diet. Nowadays, bodybuilders in general do shorter, more intense workouts and schedule more time for rest and recuperation—very different from the six-days-a-week, twice-a-day training with more exercises, sets, and reps workout schedules common during Arnold’s competitive career.

But so much in the first Encyclopedia is still accurate and relevant—the exercises described as well as the insights into what bodybuilding is all about and the mindset necessary to achieve success—that we didn’t want to call the entire book into question or imply that Arnold was “wrong” in his views about training and diet when he was competing. We are, of course, talking about the most successful bodybuilder of all time.

Arnold knew as much about how to be a bodybuilder as anyone in the 1960s and 1970s, but as time goes on, knowledge in all areas of life develops and evolves—although some truths are universal and never change. However, too much reverence for the past and how things were done can be a severe handicap when it comes to making the most of current knowledge and practices.

Looking back, Arnold first learned how to train and diet when he was a teenager in Austria. His role models and mentors were among the first generation of what we can call the original “modern” bodybuilders. The sport of bodybuilding as we know it evolved out of what were called “physical culture” contests in the 1920s and 1930s. These were events in which athletes showed off their physiques and did some kind of athletic performance—something like women’s fitness is today. Some of the competitors were gymnasts or boxers or involved in some other sport. Some were weightlifters. Over time, because of their more highly developed muscles, the weightlifters began to dominate. So, in 1939 and 1940, the first real bodybuilding contests were held, featuring these weightlifters posing and flexing onstage and performing sometimes very elaborate expert posing routines.

One of Arnold’s heroes was Mr. Universe Reg Park, who had the kind of “big man” physique Arnold most admired. I interviewed Reg several times back in the day, and he explained in detail how he trained when he first began competing—basically, like a weightlifter. He worked the whole body, top to bottom, in one workout three times a week. Most of the exercises were two-joint power movements, such as squats, bench presses, shoulder presses, deadlifts, and bent-over rows. His diet involved a lot of red meat and whole milk. The idea was to become big and strong, and detailed muscularity and definition were not yet qualities required by the judges.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the style of training and the kind of physique considered ideal gradually changed. As more gym equipment became available (Reg Park used to do bench presses lying back on a sandbag) bodybuilders began doing more one-joint isolation exercises. Instead of training the entire body in one workout, they started doing split-system workouts, hitting only certain body parts in a workout, doing a series of shorter sessions divided up over a multi-day training cycle. Joe Weider popularized many of the new techniques by describing them in what he called “Weider Principles” and helping to make them available to bodybuilders around the world.

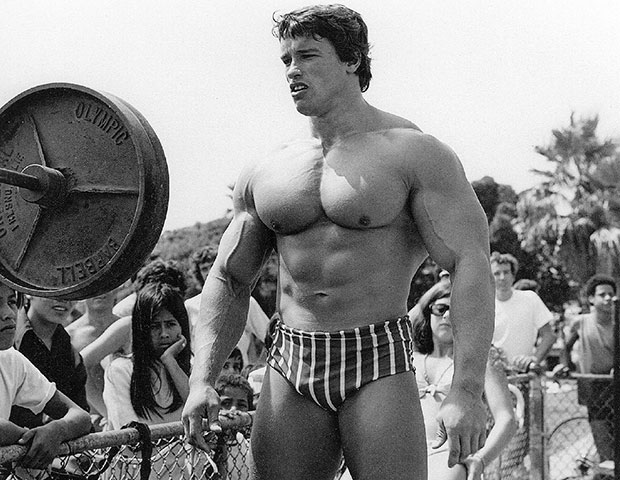

This was the level of knowledge available to Arnold at the beginning of his career. An early gym in which he trained in back in Austria didn’t have the range of equipment we expect to find today. To do incline barbell presses, he had to clean the weight and fall back against a standing incline apparatus and do his inclines from there. But he did follow a split-system routine and would, in fact, keep track of his sets and reps by marking on the wall with chalk. Unlike earlier bodybuilders, Arnold did a lot of isolation movements as well as power exercises. In fact, looking at his workouts during the 1970s, most would think he did far too many different exercises. Some even accused him of making up his own versions of exercises just to see who would end up copying him. That idea is not too far-fetched if you know how Arnold’s mind (and sense of humour) work.

As training methods continued, we began to see more complete physiques. And as diet knowledge advanced in the late 1960s and 1970s, the degree of definition and muscularity we saw in top champions increased dramatically. Look at photos of Arnold throughout his career and it’s obvious how much he learned about diet. In fact, when he first came to the US to compete in 1968, he lost to a much smaller but very much more ripped Frank Zane, who knew a lot more about definition dieting. Subsequently, Arnold moved to Los Angeles and his roommate was Frank Zane. Arnold has been described as a “learning machine,” and this is a good example of how that works.

In the 1970s, Arnold and most of his contemporaries engaged in what seems obvious today to be overtraining. It was widely accepted that you built big muscles by heavy power training but shaped and detailed them with high volume. Today, bodybuilders realize that heavy training builds the mass of larger muscle groups but that the same kind of sets and reps schemes work pretty much the same for small muscles—you just use less weight. Amazing definition and muscularity doesn’t come from high-volume endurance training. It results from effective dieting.

The evolution of diet created a lot of varied approaches during Arnold’s career. Bodybuilders such as Vince Gironda pioneered the kind of “extreme” definition dieting that later became virtually universal. But early on, judges frequently preferred big, full, and shapely physiques to lean and defined ones, so the standards of judging had to evolve alongside the ability of competitors to get ripped. In the 1970s, top bodybuilders turned to techniques such as the ketosis diet (putting the body into a state of carbohydrate deprivation) and extreme dehydration. The dehydration was needed in part because many bodybuilders were resorting to using highly androgenic steroids, which result in a lot of excessive water retention.

Another new approach, beginning in the late 1970s, was very high amounts of cardio training to burn off calories. This went on for several years and resulted in many bodybuilders showing up onstage looking drained, depleted, and flat. Endurance exercise results in the opposite effect on muscle that bodybuilders are looking for. So in his later career, Arnold was competing at as little as 235 pounds, much smaller than he would otherwise have been because of the overtraining, over-dieting approaches popular in the 1970s.

But given that Arnold is a learning machine, when we undertook to write an updated version of the Encyclopedia, he was very much aware of the changes in training and diet information that had evolved since we wrote the original. So his decision was to write the text with the approach that bodybuilding is a sport, all sports are progressive, and times and information change, and the focus of the book was to be accepting of these changes and describing them to readers, while retaining the still-valuable information and philosophy of the original version.

He also wanted to include references to and photos of more contemporary competitors, while still recognizing the champions of the past that had helped make the sport what it has become. Most sports remember and revere legendary champions of the past, and bodybuilding should do no less.

So given current knowledge, what would Arnold have done differently in his training if he had had access to more modern and effective techniques? Well, he certainly would have done shorter and more intense workouts, as bodybuilders do today. He would have done fewer exercises, sets, and reps, but with 100 percent concentration and intensity in the gym. As Mike Mentzer was fond of saying, you can train hard or you can train long, but not both. Arnold nowadays would not schedule six workout days a week, because you stimulate growth when you train but your body grows when you rest. So sufficient recuperation time is necessary for maximum development.

Overtraining was one reason Arnold, at 6'1", was at his best around 242 (according to IronMan publisher John Balik) and not 20 pounds or so heavier. It might also have been the reason his quads, huge from the side, didn’t have the shape and flare they might have had. If he had worked his triceps as hard as his biceps when he was a young bodybuilder, he might not have had to work so hard pumping them up pre-contest to be able to present a full and balanced arm. If had avoided so-called abdominal exercises such as twists and side bends, his obliques and overall waist size might have been smaller.

I mentioned above that true sports are progressive. That is, the later athletes are inevitably perform better than earlier ones. Imagine Babe Ruth able to take advantage of modern training and diet knowledge. Track star Jesse Owens was not exposed to the training techniques (or equipment) available to modern runners. Athletes as varied as golfer Tiger Woods and Formula 1 champion Michael Schumacher both enhanced their domination in their respective sports by a focus on strength training and conditioning rarely seen in the past in their respective sports.

I often see the opinion that the incredible size and development of today’s top pro bodybuilders is mostly due to increased or more sophisticated anabolic use. Certainly, athletes have learned a lot about how to use drugs most effectively, but there have been essentially no great advances in anabolic drugs in the past few decades—although the pre-contest use of GH and insulin has allowed competitors to appear onstage much bigger and fuller than in the past when excessive dehydration helped them get ripped but lose a lot of size.

No, the main reasons for such bigger champions nowadays are (1) better genetics—more really big guys getting into the sport—and (2) much more effective training involving shorter and more intense workouts, more rest, and less overtraining.

Genetics is an important factor. Larry Scott, the first Mr. Olympia, described himself as a pumped-up pencil neck who would never have won competitions just a few years later. Steve Reeves had super aesthetics and Sergio Oliva incredible symmetry, and both would have benefitted from exposure to modern techniques. But the mass and thickness of so many of today’s Olympia hopefuls is possible to a large degree because of their genetic inheritance.

Arnold was the most successful bodybuilder of his day—and in one sense of all time. But he is the first to admit that the sport has continued to develop and evolve in the years since he retired and moved on to other areas of achievement. The top pro bodybuilders are so much bigger, harder, and thicker than in the 1970s that they almost appear to be a different species. In fact, it is doubtful any of the top pros of the 1970s could win the NPC Nationals nowadays. But athletes should be evaluated in terms of their times and whom they competed against. So this takes nothing away from the icons and legends of bodybuilding from the past.

So Arnold is proud to have his name on Arnold’s New Encyclopedia of Modern Bodybuilding even though it features a lot of information techniques that were developed after he retired from bodybuilding—and which are often not those he took advantage of himself. The idea is to make the best possible and updated information available to the bodybuilders of today, an idea that is what motivated Arnold to revise and update the original Encyclopedia.