Heres the Mistake Killing Your Ab Workout

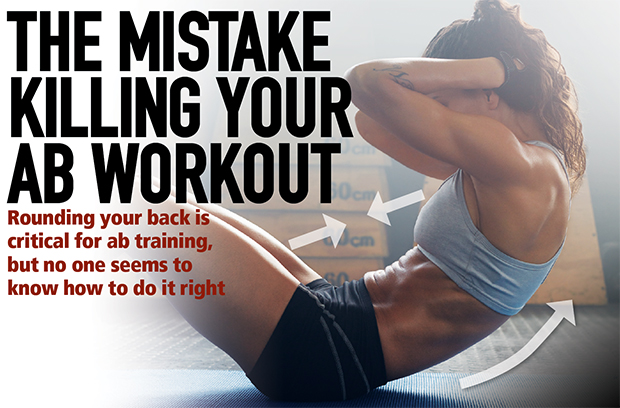

Rounding your back is critical for ab training, but no one seems to know how to do it right

When one muscle is contracting, its antagonist is being stretched—a good rule to know when working opposing muscle groups such as biceps and triceps, and quads and hamstrings. But all too many folks completely ignore it when training abs, and that stubborn fact derails ab training faster than a Clayton Kershaw fastball.

Let’s take a closer look at why it’s especially a problem with ab training and how you can fix it.

Flat Back Fever

Keeping a flat or slightly arched back is absolutely critical on every bodybuilding exercise you do for spinal safety, so over time you’ve (hopefully) perfected it. That is, every exercise exceptwhen it comes to abs and low-back movements. Here, you need to unlearn that lesson because it can make movements such as cable crunches and decline crunches essentially meaningless.

Remember, to hold a flat back you must contract your erector spinae (lower back muscles) isometrically, at the very least. Good luck trying to do that while simultaneously contracting its antagonist—the rectus abdominis—activelythrough a full range of motion. In fact, try to suck in your gut while doing a set of bent-over rows, a feat I’ve seen photographers try in vain with bodybuilders during photo shoots.

During an abdominal exercise, your goal is to physically bring the pelvis and rib cage closer to each other, which stretches the low-back musculature (erectors). You can see how an isometric contraction of the erectors, then, hinders the antagonist muscles from being able to stretch, and then contract. What often happens instead is that you hinge at the hips rather than achieve significant shortening of the rectus abdominis muscle.

The hip hinge is what you see when holding your torso in position during such movements as bent-over lateral raises, bent-over rows, and Romanian deadlifts. But a hip hinge in fact doesn’t bring your pelvis and rib cage together, and here’s where you need to distinguish between bending at the hips and bending at the waist. The former is essential for maintaining a flat back whereas the latter is necessary in low back and abdominal training.

It may help to think of your spine as not being like your highly inflexible thigh or arm bone but, rather, as the series of small vertebrae that it is, which allows a high degree of bending in either direction. That curving is in fact what you’re trying to achieve in low-back and abdominal movements. The hip-hinge, then, is the movement at the joint, not the movement along the spine that brings the rib cage and pelvis closer.

It may help to think of your spine as not being like your highly inflexible thigh or arm bone but, rather, as the series of small vertebrae that it is, which allows a high degree of bending in either direction. That curving is in fact what you’re trying to achieve in low-back and abdominal movements. The hip-hinge, then, is the movement at the joint, not the movement along the spine that brings the rib cage and pelvis closer.

Curling your spine in a controlled manner on the concentric motion of ab exercises allows your mid-back to intentionally round. If you instead keep your back locked flat or arched, you won’t be able to effectively work your midsection musculature but are far more likely to end up doing a useless hip hinge.

You see that especially on cable crunches and decline crunches: folks hip hinging instead of curling their spine under control. The muscles of the rectus abdominis shorten to cause the curl, which is the rounding effect you see in the spine. Of course, when training your lower back you simply want to do it in reverse—again, with no hip hinge. As you contract your lower back, your abs should be getting stretched. I like to think about doing it a segment or two at a time and without momentum, so you get a better idea of what the contraction should look like.

Keep the hip hinge for exercises that require it—and as far away from ab day as possible!

Keep the hip hinge for exercises that require it—and as far away from ab day as possible!

Get articles like this one delivered to your email each month by signing up for Muscle Insider’s mailing list. Just click here.