Crunch Time

Crunch Time: The only ab exercise you will ever need

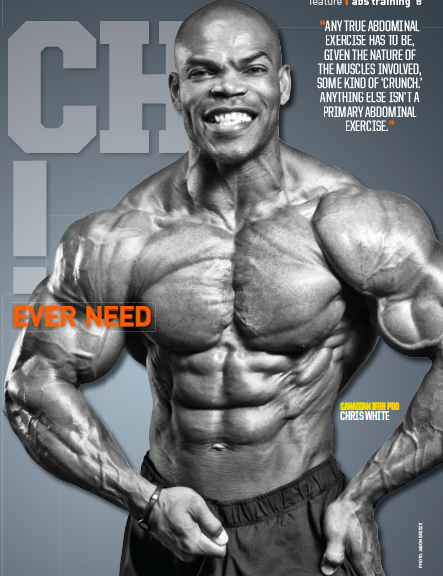

FORMER MR. UNIVERSE and successful personal trainer Charles Glass believes in keeping it simple when it comes to teaching his clients the basis of weight training. “In most cases,” says Charles, “the basics are what your clients need. It’s fine to introduce variations into the program from time to time, just for variety’s sake, but the basic exercises using basic equipment are generally what produce the best results.” Take abdominal training, for example. Rarely have so many theories been developed to explain what is one of the simplest muscle groups to train. Books have been written on the subject. However, the function of the abdominals is simply to help stabilize the torso and to draw the rib cage and pelvis together in a “crunching” movement to the front. So any true abdominal exercise has to be, given the nature of the muscles involved, some kind of “crunch.” Anything else isn’t a primary abdominal exercise. This wasn’t well understood back in the 1970s. Bodybuilders did crunches, of course. But they did a lot of other exercises that in retrospect seem little more than a waste of time and energy. “People tend to make two mistakes regarding abdominal training,” instructs Charles Glass. “Instead of pulling the rib cage and pelvis together, they think the function of the abs is to lift the entire torso, as in a traditional sit-up. Or they believe the abdominals are connected somehow to the legs, and so they try to train abs by lifting their legs into the air in a conventional leg lift.” Both these exercises, Charles tells his clients, primarily work a set of muscles called the iliopsoas or hip flexors, which attach at the lower back, cross over the pelvis, and insert in the thigh. When you do sit-ups or leg lifts, instead of your abs flexing through a full range of motion, they function instead as stabilizers, keeping your torso steady during the movement.

Your abdominals can get very tired when this demand is made of them, but you don’t get the kind of washboard abdominal development that most people hope for from this kind of training. “It’s easy to demonstrate how this works,” Charles explains. “Stand up and hold onto something for balance. Put your hand on your lower abs and lift one leg. You’ll feel that the abdominals aren’t doing anything. They aren’t involved. You’re lifting with your hip flexors, not your abs.” This type of hip flexor exercise isn’t useless. It’s a great movement for sprinters, for example, who need to be able to thrust their knees up and out with power and stamina. However, too much of this kind of effort for most people and there is danger of injury to the lower back, which is where the iliopsoas muscles arise. And back problems are the last thing most of us want as the result of physical training. “Actually,” Charles points out, “while hip fl exor exercises tend to strain the lower back, real abdominal exercises are one of the main therapies for lower back problems. When you do true crunches you strengthen the abdominals in opposition to the lower back muscles and help relieve them of excess stress and strain.” True crunches all involve a movement of the rib cage and pelvis toward one another. Pseudo-ab exercises don’t.

We’ve already seen that leglifts and sit-ups aren’t true ab exercises. Neither are slantboard sit-ups or hanging leg raises or Roman chairs. All involve either lifting the legs through a range of motion or hooking the feet under a strap or bar and lifting the torso. Every exercise of this nature involves the hip flexors as primary activators rather than the abs. “I’ve seen a lot of experienced bodybuilders who get results, or feel they get results, doing Roman chairs and other iliopsoas exercises,” admits Charles Glass. “I believe this is possible for two reasons. For one, even if you’re not doing the best kind of ab exercise, if you’re conscious of drawing the rib cage and pelvis together you can get at least partial benefit from these movements. It’s not the ideal way to train abs, it’s not very efficient, but bodybuilderswho train for 10 years or more working their abs this way can still get results.” “Another reason,” he goes on, “is that there are a lot of exercises in the gym that involve the abs that aren’t primarily ab exercises. Almost any heavy, power movement for the upper body—bench presses, shoulder presses, squats, barbell rows—require a lot of effort from the abs during the lift. If you don’t think so, try training upper body heavy when you have a pulled muscle in the abdominal region. You’ll find out in a hurry how much you depend on these muscles for almost everything you do in the gym.” “Therefore,” Charles concludes, “when you see somebody with good abs it might be mostly because of these other exercises , rather than the specific ab routine he or she is doing. Especially if they have abs that are very responsive to training. Some people have such good potential for abs, anything will bring them up.”

But top amateur and pro bodybuilders, Charles points out, are usually so strong and in such good condition that they don’t have to worry much about straining their lower backs doing hip flexor movements. This isn’t true of many of his clients—and a great many readers of MUSCLE INSIDER. So his advice is simple: “Stick to the basic ab exercises. Forget about iliopsoas movements. You don’t need them. They don’t work all that well. And they can hurt your back. It seems to me that’s plenty of reason to stay away from them.”

ABDOMINAL TRAINING ROUTINE WHEN TO TRAIN ABS

Most bodybuilders train abs at the end of their workouts, after they’ve finished with their major body parts. A few like to begin with abs, but the abdominal muscles are important in so many exercises that tiring the abs at the beginning of your training session can often lessen the

intensity of your workouts.

HOW OFTEN TO TRAIN ABS

Some bodybuilders train abs frequently, after every workout or every other workout, while others get good results working abs only once a week. It seems apparent that you can train abs more often than most other body parts without overtraining them. But unless you’re in the final stages of contest preparation, a good strategy, and one many bodybuilders adopt, is to hit them every other workout, alternating them

with calf training.

GENERAL AB-TRAINING TIPS

1. Concentrate on true ab exercises, in which the rib cage and pelvis squeeze together, rather than on hip flexor movements.

2. Try working abs at the end of your workout rather than the beginning.

3. You can work your abs more frequently than other muscles without

overtraining, but hitting abs every other workout is probably sufficient.

4. How many reps you do in a set for abs depends on how hard you “crunch” at the top of each movement. Unless your abs are already extremely tired, you should probably get at least 15 reps, but if you can do more than 25 or 30, you’re probably not getting enough intensity in each rep.

5. How many sets you do for abs depends on how well-conditioned

you are and what kind of workout you’ve just completed. The idea is to do as many sets as you can of truly intense repetitions. Try to do at least two sets of a crunching movement and two more of a reverse

crunching movement. As you get more advanced you will find you can do a few more sets. But, remember, as you get stronger you become

capable of generating additional intensity, so really advanced bodybuilders are often able to contract their abs with such power that they only need a few sets to really blast their abdominal muscles.

6. You can do a variety of different abdominal exercises, but make sure you do some crunch-type movements for the upper abs and reverse crunch-type movements for the lower abs. You can do both in one workout or alternate between workouts; just make certain you work the entire abdominal area over time.

HOW MUCH TO TRAIN ABS

Abdominal training doesn’t lend itself to a clearly defined sets-and-reps routine. Former heavyweight champ Muhammad Ali, for example,

when asked how many sit-ups he did, replied that he didn’t know. “I don’t start counting until it hurts,” was his explanation. Generally, you do as many reps for abs as you can in any given set. That could easily be 20 to 30. But there is a variable to be considered. The harder you “crunch” the muscles in a peak contraction at the top of the movement, and the longer you hold this crunch, the more quickly you’re going to tire. So by creating maximum intensity in each rep, you might find you can’t do any more than 15 to 20 in a set. As Mike Mentzer always said, you can train hard or you can train long, but you can’t do both. In the same regard, it’s hard to say how many sets any individual ought to do. Three or four sets for upper abs (crunches) and three or four for lower abs (reverse crunches) is probably more than enough. Again, it depends on what the rest of your workout has been like. After a heavy leg workout, with maximum effort on squats, you may find your abs start to cramp almost from the time you start doing your crunches. If so, let it go. There’s no use abusing a muscle that’s already near exhausted.

So the prescription for ab training comes down to this: Do as much as you can, as much as you think you need, but keep the intensity of the

movement high rather than trying to achieve maximum volume.

WEIGHTED AB MOVEMENTS?

You often see bodybuilders doing some kind of crunching movement holding onto a heavy weight plate across their chests. This isn’t really necessary. Heavy weight training, such as benches or squats, forces your abs to deal with serious poundages. The point of ab training is to work your abs through a full range of motion for a number of reps and to get a maximum peak contraction at the top. The plate on your chest doesn’t provide as much resistance as a heavy barbell when you’re squatting, and it doesn’t really work directly against the line of contraction of the movement—you’re not lifting up, you’re crunching the rib cage and the pelvis toward each other. So this isn’t a technique that’s particularly recommended. And, by the way, if you want to do abdominal exercises against extra resistance, check out the hanging reverse crunches described below. Those provide more than enough resistance for anyone.

RECOMMENDED ABDOMINAL EXERCISES

There are a lot of different exercises used for abdominal training. Below are those that are considered the most basic, fundamental, and useful.

CRUNCHES: Lie on your back on the floor, with your legs across a bench in front of you. You can put your hands behind your neck or keep them in front of you, whichever you prefer. Curl your shoulders and trunk upward toward your knees. Don’t try to lift your entire back up off the floor, just roll forward and crunch your rib cage toward your pelvis. At the top of the movement, deliberately give an extra squeeze of the abs to achieve total contraction, then release and lower your shoulders back to the starting position. This isn’t a movement you do quickly. Do each rep deliberately and under control.

Variation: You can vary the angle of stress on your abdominals by raising your foot position. Instead of putting your legs across a bench, try lying on the floor and placing the soles of your feet against a wall at whatever height feels most comfortable.

REVERSE CRUNCHES: This exercise is best done lying on a bench press bench that has a rack at one end. Lie on your back on the bench and reach up behind you to hold the rack for support. Bend your knees and bring them up as far toward your face as you can without lifting your pelvis off the bench. From this starting position, bring your knees up as close to your face as you can, with the pelvis coming up off the bench and crunching up toward the rib cage. Hold for a moment at the top and deliberately squeeze the ab muscles for full contraction. Slowly lower your knees until your pelvis comes to rest on the bench again. (Don’t lower your legs any further than this. You aren’t doing leg raises.) Again, do this movement deliberately and under control rather than doing a lot of quick reps

HANGING REVERSE CRUNCHES: This is another version of reverse crunches, only you do it hanging by your hands from a bar or resting on your forearms on a hanging leg-raise bench instead of lying on a bench. Get into the hanging position and bring your knees up as far as possible. From this starting position, raise your knees up as far as possible toward your head, rolling yourself upward into a ball. At the top of the movement, hold and crunch the ab muscles together for full contraction, then lower your knees to the starting position with the knees pulled up.Again, don’t lower your legs beyond this starting point.

Variation: A lot of people and most bodybuilders (because of the mass of their legs) can hardly do any hanging reverse crunches. An easier variation is to lie head-upward on a slantboard. This gives you more resistance than reverse crunches on a flat bench, but you can dial in the amount of resistance you want by the angle at which you set the slantboard.

CABLE CRUNCHES: This is an exercise you used to see much more in the “old days” than you do today, but it’s an effective one. Attach a rope to an overhead pulley. Kneel down and grasp the rope with both hands. Holding the rope in front of your forehead, bend and curl downwards, bringing your head to your knees and feeling the abdominals crunch together. Hold the peak contraction at the bottom, then release and come back up to the starting position. Make sure the effort involved is made with the abs. Don’t pull down with the arms.

MACHINE CRUNCHES: A great many bodybuilders feel that machines are unnecessary when it comes to ab training. But others swear by some of the ab training equipment currently available. Charles Glass, for example, often has his clients use a Nautilus crunch machine. In all cases, however, concentrate on feeling the rib cage and the pelvis

squeeze together as the abdominals contract. If you can’t achieve this

feeling, the piece of equipment you are using may not be suited to your individual needs.